Kicked Off the Land by Lizzie Presser c/o The New Yorker

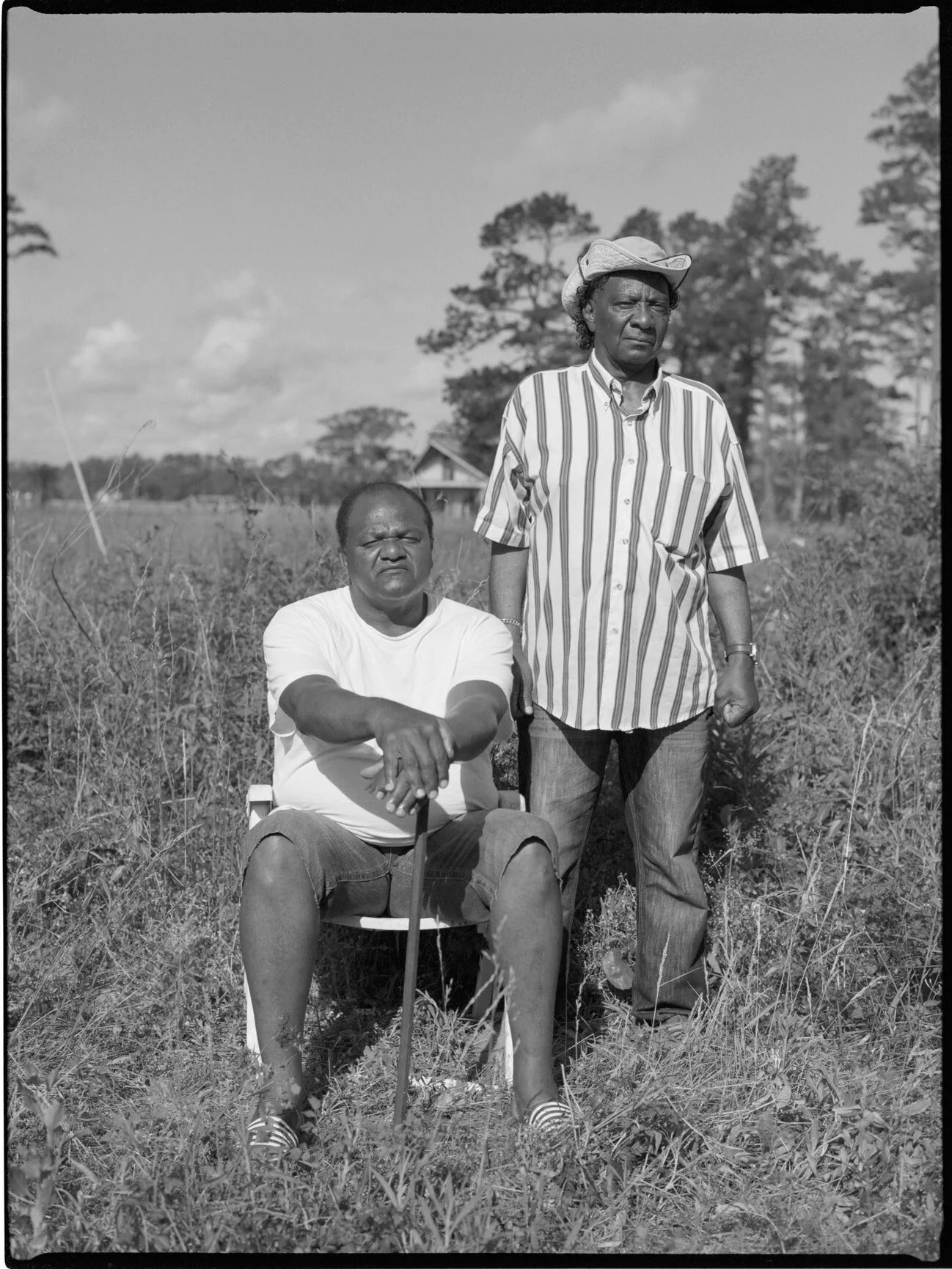

Licurtis Reels, left, and Melvin Davis, right, on Silver Dollar Road. Photograph by Al J. Thompson for The New Yorker

Overview

A historical account of the violent, colonial dispossession of Black land told through the story of Melvin and Licurtis Reeles, sons of Gertrude Reeles and owners of 65 acres along Silver Dollar Road in North Carolina.

Anecdotes of Lost Land

(1) On the coast of North Carolina, I met Billy Freeman, who grew up working in the parking lot of his uncle’s beachside dance hall, Monte Carlo by the Sea. His family, which once owned thousands of acres, ran the largest black beach in the state, with juke joints and crab shacks, an amusement park, and a three-story hotel. But, over the decades, developers acquired interests from other heirs, and, in 2008, one firm petitioned the court for a sale of the whole property. Freeman attempted to fight the partition for years. “I didn’t want to lose the land, but I felt like everybody else had sold,” he told me. In 2016, the beach, which covered a hundred and seventy acres, was sold to the development firm for $1.4 million. On neighboring beaches, that sum could buy a tiny fraction of a parcel so large. Freeman got only thirty thousand dollars.

(2) In one case that I examined, the mining company PCS Phosphate forced the sale of a forty-acre plot, which contained a family cemetery, against the wishes of several heirs, whose ancestors had been enslaved on the property. (A spokesperson for the company told me that it is a “law-abiding corporate citizen.”)

(3) When Jessica Wiggins’s uncle called her to say that a man was trying to buy his interest in their family’s land, she didn’t believe him; he had dementia. Then, in 2015, she learned that a company called Aldonia Farms had purchased the interests of four heirs, including her uncle, and had filed a partition action. “What got me was we had no knowledge of this person,” Wiggins told me, of the man who ran Aldonia. (Jonathan S. Phillips, who now runs Aldonia Farms, told me that he wasn’t with the company at the time of the purchase, and that he’s confident no one would have taken advantage of the uncle’s dementia.) Wiggins was devastated; the eighteen acres of woods and farmland that held her great-grandmother’s house was the place that she had felt safest as a child. The remaining heirs still owned sixty-one per cent of the property, but there was little that they could do to prevent a sale. When I visited the land with Wiggins, her great-grandmother’s house had been cleared, and Aldonia Farms had erected a gate. Phillips told me, “Our intention was not to keep them out but to be good stewards of the property and keep it from being littered on and vandalized.”

Threats to Black Land

(1) A partition action — In the course of generations, heirs tend to disperse and lose any connection to the land. Speculators can buy off the interest of a single heir, and just one heir or speculator, no matter how minute his share, can force the sale of an entire plot through the courts.

(2) The Torrens Act — Under Torrens, Shade didn’t have to abide by the formal rules of a court. Instead, he could simply prove adverse possession to a lawyer, whom the court appointed, and whom he paid. The Torrens Act has long had a bad reputation, especially in Carteret. “It’s a legal way to steal land,” Theodore Barnes, a land broker there, told me. The law was intended to help clear up muddled titles, but, in 1932, a law professor at the University of North Carolina found that it had been co-opted by big business. One lawyer said that people saw it as a scheme “whereby rich men could seize the lands of the poor.” Even Shade’s lawyer, Nelson Taylor, acknowledged that it was abused; he told me that his own grandfather had lost a fifty-acre plot to Torrens. “First time he knew anything about it was when somebody told him that he didn’t own it anymore,” Taylor said. “That was happening more often than it ever should have.”

(3) Tax sale has a long history in the dispossession of heirs’-property owners. In 1992, the N.A.A.C.P. accused local officials of intentionally inflating taxes to push out black families on Daufuskie, a South Carolina sea island that has become one of the hottest real-estate markets on the Atlantic coast. Property taxes had gone up as much as seven hundred per cent in a single decade. “It is clear that the county has pursued a pattern of conduct that disproportionately displaces or evicts African-Americans from Daufuskie, thereby segregating the island and the county as a whole,” the N.A.A.C.P. wrote to county officials. Nearby Hilton Head, which as recently as two decades ago comprised several thousand acres of heirs’ property, now, by one estimate, has a mere two hundred such acres left. Investors fly into the county each October to bid on tax-delinquent properties in a local gymnasium.

Key Takeaways

On the scale and impact of Black land loss:

Between 1910 and 1997, African-Americans lost about ninety per cent of their farmland. This problem is a major contributor to America’s racial wealth gap; the median wealth among black families is about a tenth that of white families. Now, as reparations have become a subject of national debate, the issue of black land loss is receiving renewed attention. A group of economists and statisticians recently calculated that, since 1910, black families have been stripped of hundreds of billions of dollars because of lost land.

Gertrude Reels, on the family property. Photograph by Al J. Thompson for The New Yorker

On the failure of white agreements and the promise of Black self-establishments:

On January 12, 1865, just before emancipation, the Union Army general William Tecumseh Sherman met with twenty black ministers in Savannah, Georgia, and asked them what they needed. “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land,” their spokesperson, the Reverend Garrison Frazier, told Sherman. Freedom, he said, was “placing us where we could reap the fruit of our own labor.” Sherman issued a special field order declaring that four hundred thousand acres formerly held by Confederates be given to African-Americans—what came to be known as the promise of “forty acres and a mule.” The following year, Congress passed the Southern Homestead Act, opening up an additional forty-six million acres of public land for Union supporters and freed people.

The promises never materialized. In 1876, near the end of Reconstruction, only about 5% of black families in the Deep South owned land. But a new group of black landowners soon established themselves. Many had experience in the fields, and they began buying farms, often in places with arid or swampy soil, especially along the coast. By 1920, African-Americans, who made up ten per cent of the population, represented 14% of farm owners in the South.

On white violence against Black land:

A white-supremacist backlash spread across the South. At the end of the nineteenth century, members of a movement who called themselves Whitecaps, led by poor white farmers, accosted black landowners at night, whipping them or threatening murder if they didn’t abandon their homes. In Lincoln County, Mississippi, Whitecaps killed a man named Henry List, and more than fifty African-Americans fled the town in a single day. Over two months in 1912, violent white mobs in Forsyth County, Georgia, drove out almost the entire black population—more than a thousand people. Ray Winbush, the director of the Institute for Urban Research, at Morgan State University, told me, “There is this idea that most blacks were lynched because they did something untoward to a young woman. That’s not true. Most black men were lynched between 1890 and 1920 because whites wanted their land.”

On modern, legally-sanctioned violence against Black land:

By the second half of the twentieth century, a new form of dispossession had emerged, officially sanctioned by the courts and targeting heirs’-property owners without clear titles. These landowners are exposed in a variety of ways. They don’t qualify for certain Department of Agriculture loans to purchase livestock or cover the cost of planting. Individual heirs can’t use their land as collateral with banks and other institutions, and so are denied private financing and federal home-improvement loans. They generally aren’t eligible for disaster relief. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina laid bare the extent of the problem in New Orleans, where twenty-five thousand families who applied for rebuilding grants had heirs’ property. One Louisiana real-estate attorney estimated that up to a hundred and sixty-five million dollars of recovery funds were never claimed because of title issues.

On getting ahead of the fight for heir’s property:

Heirs are rarely aware of the tenuous nature of their ownership. Even when they are, clearing a title is often an unaffordable and complex process, which requires tracking down every living heir, and there are few lawyers who specialize in the field. Nonprofits often pick up the slack. The Center for Heirs’ Property Preservation, in South Carolina, has cleared more than two hundred titles in the past decade, almost all of them for African-American families, protecting land valued at nearly fourteen million dollars. Josh Walden, the center’s chief operating officer, told me that it had mapped out a hundred thousand acres of heirs’ property in South Carolina. He said that investors hoping to build golf courses or hotels can target these plots. “We had to be really mindful that we didn’t share those maps with anyone, because otherwise they’d be a shopping catalogue,” he told me. “And it’s not as if it dries up. New heirs’ property is being created every day.”

On the state and real estate industry conspiring against Black land ownership:

The Reelses knew that if condos or a marina were built on the waterfront the remaining fifty acres of Silver Dollar Road could be taxed not as small homes on swampy fields but as a high-end resort. If they fell behind on the higher taxes, the county could auction off their property. “It would break our family right up,” Melvin told me. “You leave here, you got no more freedom.”This kind of tax sale has a long history in the dispossession of heirs’-property owners. In 1992, the N.A.A.C.P. accused local officials of intentionally inflating taxes to push out black families on Daufuskie, a South Carolina sea island that has become one of the hottest real-estate markets on the Atlantic coast. Property taxes had gone up as much as seven hundred per cent in a single decade. “It is clear that the county has pursued a pattern of conduct that disproportionately displaces or evicts African-Americans from Daufuskie, thereby segregating the island and the county as a whole,” the N.A.A.C.P. wrote to county officials. Nearby Hilton Head, which as recently as two decades ago comprised several thousand acres of heirs’ property, now, by one estimate, has a mere two hundred such acres left. Investors fly into the county each October to bid on tax-delinquent properties in a local gymnasium.

On the colonial spirit of real estate development:

When real-estate agents or speculators came to the shore, Melvin tried to scare them away. A developer told me that once, when he showed the property to potential buyers, “Melvin had a roof rack behind his pickup, jumped out, snatched a gun out.” It wasn’t the only time that Melvin took out his rifle. “You show people that you got to protect yourself,” he told me. “Any fool who wouldn’t do that would be crazy.” His instinct had always been to confront a crisis head on. When hurricanes came through and most people sought higher ground, he’d go out to his trawler and steer it into the storm.

The Reels family began to believe that there was a conspiracy against them. They watched Jet Skis crawl slowly past in the river and shiny S.U.V.s drive down Silver Dollar Road; they suspected that people were scouting the property. Melvin said that he received phone calls from mysterious men issuing threats. “I thought people were out to get me,” he said. Gertrude remembers that, one day at the farmers’ market, a white customer sneered that she was the only thing standing in the way of development.

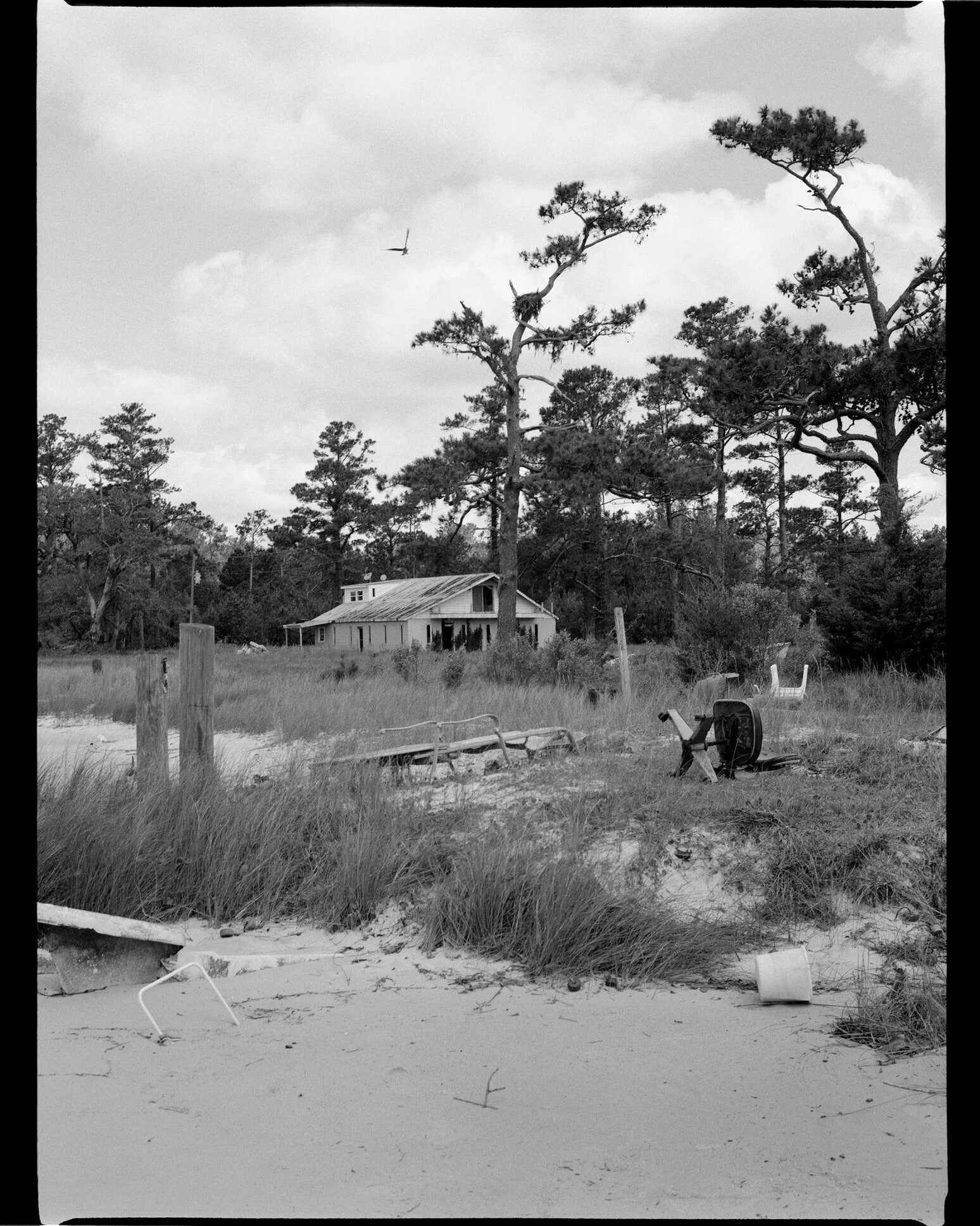

One of the dilapidated structures on the contested property. Photograph by Al J. Thompson for The New Yorker

On the effect of Black land dispossession on mental health:

Licurtis didn’t talk about the case, and tried to hide his stress. But, Mamie told me, “you could see him wearing it.” Occasionally, she would catch a glimpse of him pacing the road early in the morning. When he first understood that he could face time in jail for remaining in his house, he tried removing the supports underneath it, thinking that he could hire someone to wrench the foundation from the mud and move it elsewhere. Gertrude wouldn’t allow him to go through with it. “You’re not going with the house nowhere,” she told him. “That’s yours.”

At 4 a.m. on a spring day in 2007, Melvin was asleep in his apartment above the club when he heard a boom, like a crash of thunder. He went to the shore and found that his trawler, named Nancy J., was sinking. Yellow plastic gloves, canned beans, and wooden crab boxes floated in the water. There was a large hole in the hull, and Melvin realized that the boom had been an explosion. He filed a report with the sheriff’s office, but it never confirmed whether an explosive was used or whether it was an accident, and no charges were filed. Melvin began to wake with a start at night, pull out his flashlight, and scan the fields for intruders.

By the time of the brothers’ hearing in 2011, Melvin had lost so much weight that Licurtis joked that he could store water in the caverns by his collarbones.

On partition sales as a weapon of the judicial system:

One of the most pernicious legal mechanisms used to dispossess heirs’-property owners is called a partition action. In the course of generations, heirs tend to disperse and lose any connection to the land. Speculators can buy off the interest of a single heir, and just one heir or speculator, no matter how minute his share, can force the sale of an entire plot through the courts. Andrew Kahrl, an associate professor of history and African-American studies at the University of Virginia, told me that even small financial incentives can have the effect of turning relatives against one another, and developers exploit these divisions. “You need to have some willing participation from black families—driven by the desire to profit off their land holdings,” Kahrl said. “But it does boil down to greed and abuse of power and the way in which Americans’ history of racial inequality can be used to the advantage of developers.” As the Reels family grew over time, the threat of a partition sale mounted; if one heir decided to sell, the whole property would likely go to auction at a price that none of them could pay.

When courts originally gained the authority to order a partition sale, around the time of the Civil War, the Wisconsin Supreme Court called it “an extraordinary and dangerous power” that should be used sparingly. In the past several decades, many courts have favored such sales, arguing that the value of a property in its entirety is greater than the value of it in pieces. But the sales are often speedy and poorly advertised, and tend to fetch below-market prices.

Melvin’s club, Fantasy Island. Photograph by Al J. Thompson for The New Yorker

On the clear racial bias of partisan sales:

Hundreds of partition actions are filed in North Carolina every year. Carteret County, which has a population of seventy thousand, has one of the highest per-capita rates in the state. I read through every Carteret partition case concerning heirs’ property from the past decade, and found that 42% of the cases involved black families, despite the fact that only 6% of Carteret’s population is black. Heirs not only regularly lose their land; they are also required to pay the legal fees of those who bring the partition cases.

On the legislative\ action and political reform to unsafe real estate practices:

Thomas W. Mitchell, a property-law professor at Texas A. & M. University School of Law, has drafted legislation aimed at reforming this system, which has now passed in fourteen states. He told me that heirs’-property owners, particularly those who are African-American, tend to be “land rich and cash poor,” making it difficult for them to keep the land in a sale. “They don’t have the resources to make competitive bids, and they can’t even use their heirs’ property as collateral to get a loan to participate in the bidding more effectively,” he said.

His law, the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act, gives family members the first option to buy, sends most sales to the open market, and mandates that courts, in their decisions to order sales, weigh non-economic factors, such as the consequences of eviction and whether the property has historic value.

North Carolina is one of eight states in the South that has held out against these reforms. The state also hasn’t repealed the Torrens Act. It is one of fewer than a dozen states where the law is still on the books.

Last year, Congress passed the Agricultural Improvement Act, which, among other things, allows heirs’-property owners to apply for Department of Agriculture programs using nontraditional paperwork, such as a written agreement between heirs. “The alternative documentation is really, really important as a precedent,” Lorette Picciano, the executive director of Rural Coalition, a group that advocated for the reform, told me. “The next thing we need to do is make sure this happens with fema, and flood insurance, and housing programs.” The bill also includes a lending program for heirs’-property owners, which will make it easier for them to clear titles and develop succession plans. But no federal funding has been allocated for these loans.

On the unrelenting optimism of Black land ownership and co-operation being the key:

Melvin told me that he’d held on for his family, and for himself, too. But away from the others his weariness showed. He acknowledged that he was worried about what would happen, his voice almost a whisper. “They can’t keep on doing this. There’s got to be an ending somewhere,” he said.

A few days later, Gertrude threw her sons a party, and generations of relatives came. The family squeezed together on her armchairs, eating chili and biscuits and lemon pie. Mamie gave a speech. “We gotta get this water back,” she said, stretching her arms wide. “We gotta unite. A chain’s only as strong as the links in it.” The room answered, “That’s right.” The brothers, who were staying with their mother, kept saying, “Once we get this land stuff sorted out . . .” Relatives who had left talked about coming back, buying boats and go-karts for their kids. It was less a plan than a fantasy—an illusion that their sense of justice could overturn the decision of the law.

The brothers hadn’t stepped onto the waterfront since they’d been back. The tract was a hundred feet away but out of reach. Fantasy Island was a shell, the plot around it overgrown. Still, Melvin seemed convinced that he would restore it. “Put me some palm trees in the sand and build some picnic tables,” he said.

After the party wound down, I sat with Licurtis on his mother’s porch as he gazed at his house, which was moldy and gutted, its frame just visible in the purple dusk. He reminisced about the house’s wood-burning heater, the radio that he’d always left playing. He said that he planned to build a second story and raise the house to protect it from floods. He wanted a wraparound deck and big windows. “I’ll pour them walls solid all the way around,” he said. “We’ll bloom again. Ain’t going to be long.”