The First Moral Panic: London, 1744 by Matthew Wills c/o JSTOR

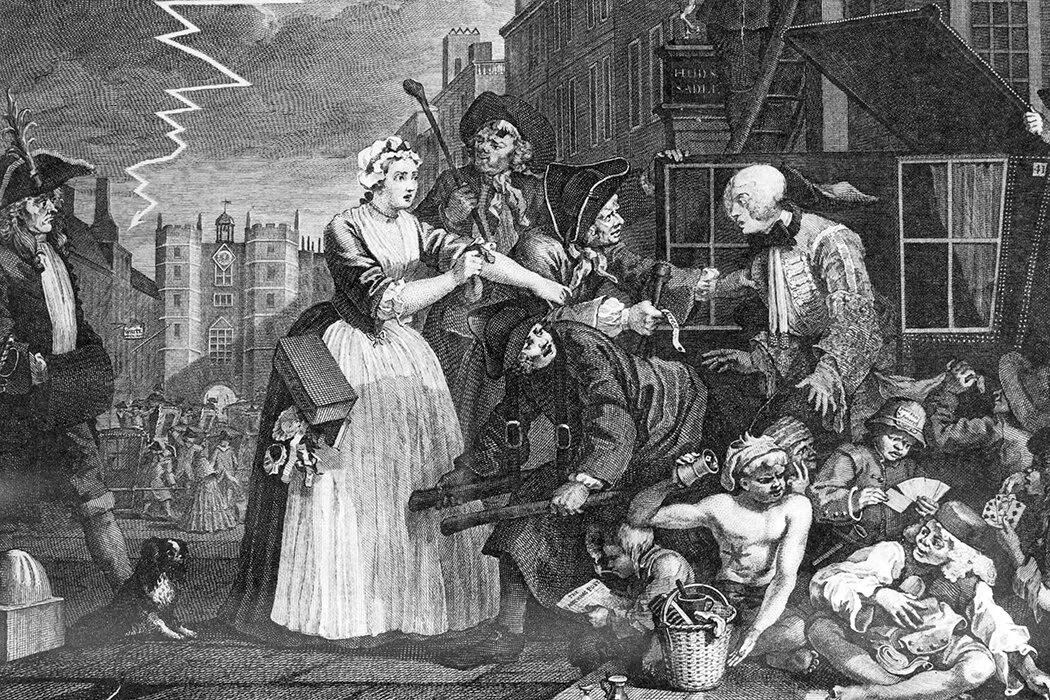

A man faces arrest in a plate from William Hogarth's The Rake's Progress, 1735 via Wikimedia Commons

Overview

The late summer crime wave of 1744 London sparked an intense moral panic about crime that burnt itself out by the new year. But not before heads rolled.

Editor’s Takeaway: Media Disruption + Validation Culture = Moral Panic

How much does the media influence our perception of crime, the criminal justice system, and the police? These issues have a long history. Richard Ward calls a 1744 London crime wave the earliest example of the media whipping up a moral panic about street crime.

Moral panics are instances of mass fear of something said to threatened the very basis of society, whether that’s witchcraft, an unconventional aspect of sexuality, crime, or something else.

The 6 stages of moral panic:

A crime or series of crimes garner(s) media attention.

The media hypes the threat.

As a result more news about crime, more crime gets reported to the police.

The crime rate is therefore judged to be higher than thought by media and law enforcement.

New and heavier controls and punishment measures are introduced.

The panic fades away in a couple of months, but the new methods for controlling and punishing become the norm.

Fear of crime doesn’t start in a vacuum: there were robberies, but it was the decision of editors and publishers to make them news that made it a full-fledged moral panic.

Editor’s Takeaway: The news should not be fantastic.

By the second half of 1744, exciting foreign news which had dominated newspaper columns, like that of the War of Jenkin’s Ear and the War of Austrian Succession, was drying up. The dearth of exciting news from abroad had to be replaced with something. So suddenly the streets were “swarming” with criminals “infesting” the city. In a succinct turn of phrase one victim was threatened with being cut “as small as sausages.”

Editor’s Takeaway: News media isn’t present, it focuses on the fear of tomorrow rather than present healing.

Once the problem was hyped, questions about what should be done about it arose in the papers of November and December of 1744. The middle-class reading public’s opinion was firmly on the side of cracking down hard. Patrols were instituted (London’s Metropolitan Police Service wouldn’t be instituted until 1829). Rewards were offered by civil and ecclesiastical authorities. People were prosecuted. And, then, by January 1745, the media was onto other topics.

The shift was so abrupt, writes Ward, that “no metropolitan newspaper provided a report of the eighteen malefactors executed at Tyburn on Christmas Eve,” among them Black Boy Alley gang members. This, mind you, when executions were rather rowdy public entertainments. Then again, this sudden shift in attention is typical of those periodic moral panics. Heads roll, and the moralists move on to other ways of scaring people.