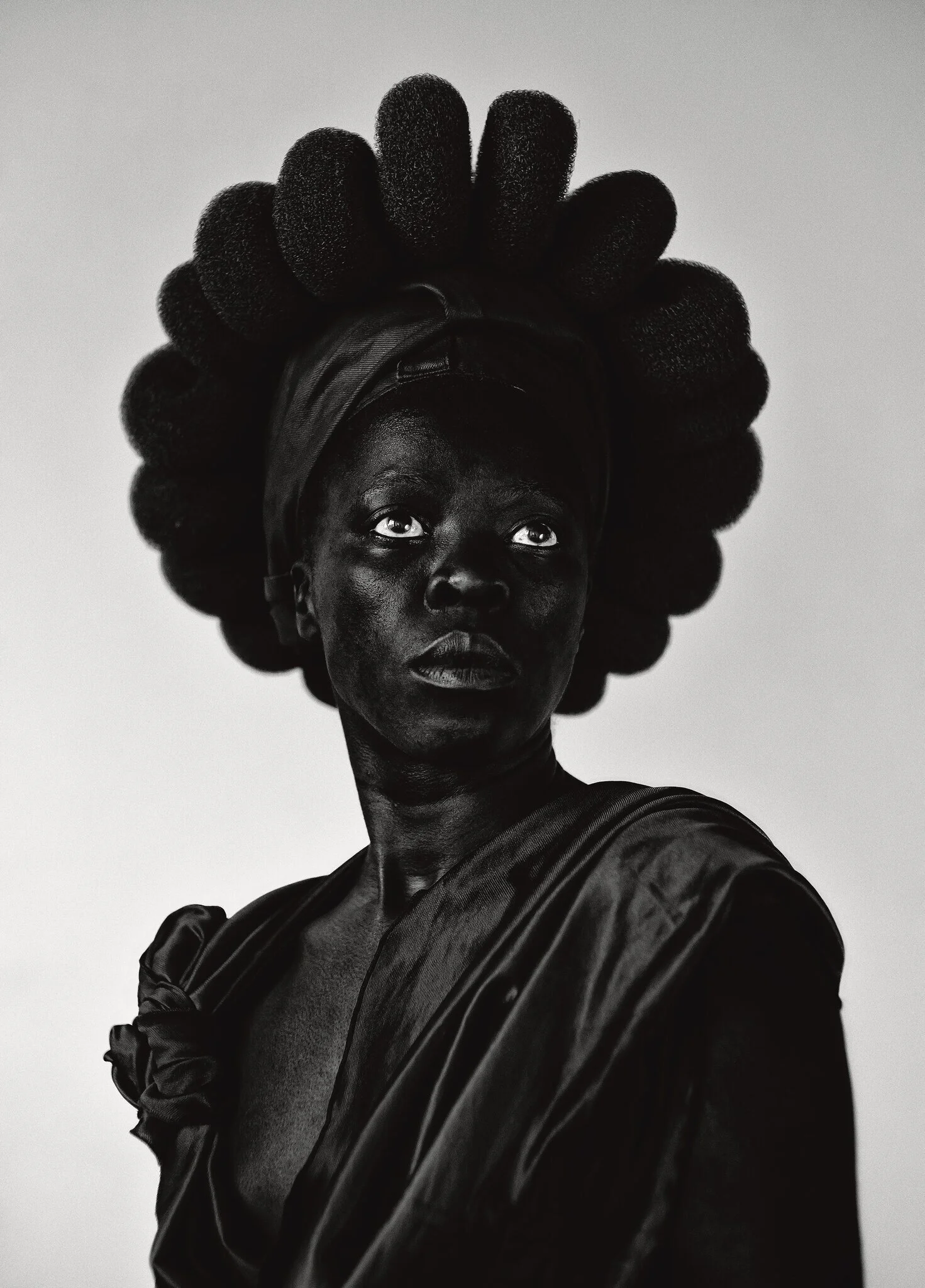

Seeing Black Futures by Jenna Wortham and Kimberly Drew c/o The New York Times

Overview

Black culture is flourishing. Jenna Wortham and Kimberly Drew want to preserve it. This essay and the portfolio below are adapted from “Black Futures,” to be published in December by One World, an imprint of Random House.

Key Takeaways

On emerging technologies and the erasure of Black history:

“These platforms encourage quantity over quality and make it increasingly difficult to access past posts. Already some of the most important reservoirs of modern Black culture, including Vine, a short-form video site that predated TikTok, or BlackPlanet, a social-networking site built specifically for Black people, have shuttered or faded from popular use. In some cases, the blogs, photos and clips created and exchanged on social platforms have disappeared from view. A recent update to Myspace, a social site that many Black musicians relied on, lost a trove of data some estimated to be as large as 53 million songs.

Online, there exists an inherent tension between remembering and forgetting that is particularly tormented, given how little agency we have over how information and memories are stored. Right now it is possible to download archives from Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for future reference, but it’s hard to imagine that anyone is doing so with regularity. With social platforms, there is newly shared culture, and in effect, shared history, but it is one that is vulnerable to a loss as arbitrary as a server migration or company sale.”

On the innate subjectivity of archival work and thus the inherent need for all to participate in it:

“We set out on this project with a keen awareness that all archives are incomplete because they rely on the priorities and preferences of the authors and collectors. We called on the wisdom of Saidiya Hartman, a professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University, who writes in her preliminary note to ‘Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments’ that ‘every historian of the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern and the enslaved is forced to grapple with the power and authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known, whose perspective matters and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor.’ One solution, embedded within ‘Black Futures,’ is encouraging our readers to see the book as an invitation to document our present as they see fit, too.”